FILM ANALYSIS TOOLS

Bilingual glossary of film editing and analisis terms (pdf / htm)

| English | Español |

| The Columbia Film Language Glossary Springhurst “Basic glossary of Film Terms AMC (American Multi-Cinema) web site | Léxico cinematográfico para alumnos de Wesleyan El lenguaje del cine INAI CINE: Glosario de términos cinematográficos básicos Glosario de cine (Ministerio de Educación) |

EXCERPTS FROM OUR FEATURE FILMS

Luis Buñuel, Chien andalou (1928)

- Introduction

- Vermeer, The Lacemaker (compare: Johannes Vermeer, “The Lacemaker,” 1699)

- Hands and illusions (compare: Federico García Lorca, “Severed hands” and

- Putrified donkeys (“putrefactos”) (click here to read about the legendary donkey, immortalized by the Andalusian poet, Juan Ramón Jiménez, in his book Platero y yo)

- Doppelganger (compare drawings in black and white by Federico García Lorca)

- Moths

- Millet’s “Angelus” (click here to see how Buñuel and Salvador Dalí maintained an ongoing dialogue Millet’s theme)

- Shades of surrealism in recent cinema?:

As Roger Ebert states, in,”a man has fallen in love with a woman who does not exist, and now he cries out harshly against the real woman who impersonated her.” See how Alejandro Amenábar appropriates one of the signature moments in Hitchcock’s masterpiece and see how both of them recall a technique used by Buñuel decades prior:

Luis Buñuel, Los olvidados / The Young and the Damned (1950)

- Opening scene

- The blind man’s retribution

- Pedro’s dream

- Juxtapositions: “Ojitos” with the blind man, Pedro with his chickens

- Pedro’s mother to the police: “Punish him!” (and fade out/in)

- His mother visit’s Pedro in his cell

- Pedro, eggs and chickens in the reform school

- The blind man counts his coins

- Pedro’s death: the donkey

- Pedro’s death: the chicken

- Finale

Buñuel’s auteurism: the shots included on this page should help you think about Buñuel’s personal approach to cinema

Luis Buñuel,Viridiana (1961)

- Part 1: Fernando Rey and the myth of Don Juan – See “La formación de un mito: Don Juan”

- “Esta noche habrá que hacer algo especial como despedida” / “Tonight will be a special night” (03:29)

- “Esta noche mientras dormías has sido mía” / “I made you mine while you slept” (01:10)

- “Dile Ramona que le he mentido” / “Ramona, tell her that I lied” (0:19)

- “Todo lo que te dije es mentira...” / “Everything I told you is a lie” (0:35)

- “Tú tampoco me crees, Ramona” / “You don’t believe me either, Ramona” (0:22)

- Viridiana takes leave, Don Jaime writes his last will (0:48)

- Part 2: Viridiana and Spanish catholicism

- Arma Christi (0:54)

- Viridiana leads the procession of the wretched (1, 2) (0:51, 0:26) – Ver Francisco de Goya, “La peregrinación de San Isidro” (1, 2)

- Montage: Viridiana and Jorge both work their respective fields (02:22) – Ver Jean-François Millet’s “L’Angelus” (1857-59)

- The leper-bride and the dove’s feathers (01:01)

- The Last Supper (01:16)

- Part 3: Social collectives, natural human impulses and the moral of the story?

- Final scene (04:32)

Luis Buñuel, El ángel exterminador / Exterminating Angel (1962)

- The Buñuelian bourgeoisie and its “discreet charm”

- Bourgeois theatricalities and repeat performances:

- Announcing the performativity of bourgeois (00:23)

- Repetitions from a different camera angle (01:32)

- The use of irony (00:16)

- “¡Qué buen oído tienen!” (“You sure hear well!”) (00:38)

- In the end, it was all a performance, so let’s repeat with a different outcome (02:13)

- Fetishes and the absurd

- Shavers, mirrors, legs (01:15)

- Females and mirrors in art: Picasso, “Woman combing herself” (1906); “Woman in front of a mirror” (1932; see MOMA interpretation of this painting); Norman Rockwell, “Girl before a mirror” (1954)

- Lover’s suicide in the closet (02:31)

- Formal analysis: how Buñuel dissects, organizes, constructs social relations with his camera

Luis García Berlanga, ¡Bienvenido Mr. Marshall! / Welcome Mr. Marshall! (1953)

- Introduction

- Hierarchies and authorities: social codes and official and unofficial protocols / Jerarquías y autoridades: códigos sociales; protocolos oficiales y uficiosos

- El Señor Delegado and don Paco (el “señor alcalde” / the mayor) (1’34”)

- “Bellezas de España” (0’26”)

- Don Paco desde el balcón (from the balcony): “El alcade vuestro que soy…” (5’50”)

- Celebrations, festivals and community / Celebraciones, fiestas y comunidad (comunitas)

- The arrival of the “first locomotive” (0’13”). Compare: Jenaro Pérez Villaamil,”Inauguración del ferrocarril” (1852)

- Desfile (parade): “Americanos, os recibimos con alegría…” (“Americans, we receive you with joy”) (1’47”; Words to the song)

- Foregrounding performativity / framing the Spanish musicals of the 1950s: Lolita Sevilla as “Carmen Vargas” on stage

- “Del Río vengo…” (1’42”)

- “Niña, asómate que te vean los americanos” (“Give the Americans a good look at you, kid”; 0’10”)

- “La maldición gitana” (“The Gypsy’s curse”; 1’56”)

- Lolita Sevilla singing a paso doble “Percheles” in the movie Malaqueña offers one of many examples of how folklore was was presented in popular/comercial cinema of the 1950s, devoid of any critical, self-conscious filtering or framing. “Malagueña” is the name of a woman from the Andalusian city of Málaga. In this song, Lolita Sevilla extols the local color and traditional charm of a characteristically Andalusian neighborhood in Málaga named “El Perchel.” She does so in terms that would appeal to tour operators seeking clients from abroad.

- Masks, clowns, farse and other modes of foregrounding the artificiality of the town’s “performance” ( alienation, distancing techniques) / Máscaras, payasos, la farsa y otras estrategias para ostentar la artificialidad del espectáculo que el pueblo piensa montar (técnicas de distanciamiento/alienación)

- Manolo sells his singer (0’16”)

- Don Cosme: “paz y espíritu, y esto ha de ser nuestro regalo” (“peace and spirit; this will be our gift”) (0’39”)

- Don Paco: “Hay que hacer algo” (“We’ve got to do something”; 0’23”)

- Don Emilio’s project for the “fuente” (fountain; 1’03”)

- Manolo “el americano” (rehearsal for “Mr. Marshall’s” arrival ceremony; 0’52”)

- Significant examples of Berlanga’s film editing (cuts) / Ejemplos significativos del montaje de Berlanga (los cortes):

- “Llega el Señor Delegado!” (“The Delegate is arriving!”) (0’58”)

- From the “Señor Delegado” to “Carmen Vargas” (0’19”)

- From Manolo to don Cosme: “¿Que si regalan cosas los americanos?” (If American give gifts…?”; 0’17”)

- From don Cosme to don Luis: “¿Qué son esos americanos?” (“Who are those Americans?”; 0’16”)

- From don Luis to la señorita Eloísa: “¿Qué son esos americanos?” (“Who are those Americans?”; 0’16”)

- From don Cosme to the newsreel: “¿Qué nos van a dar los americanos?” (“What can Americans give us?”; 0’21”

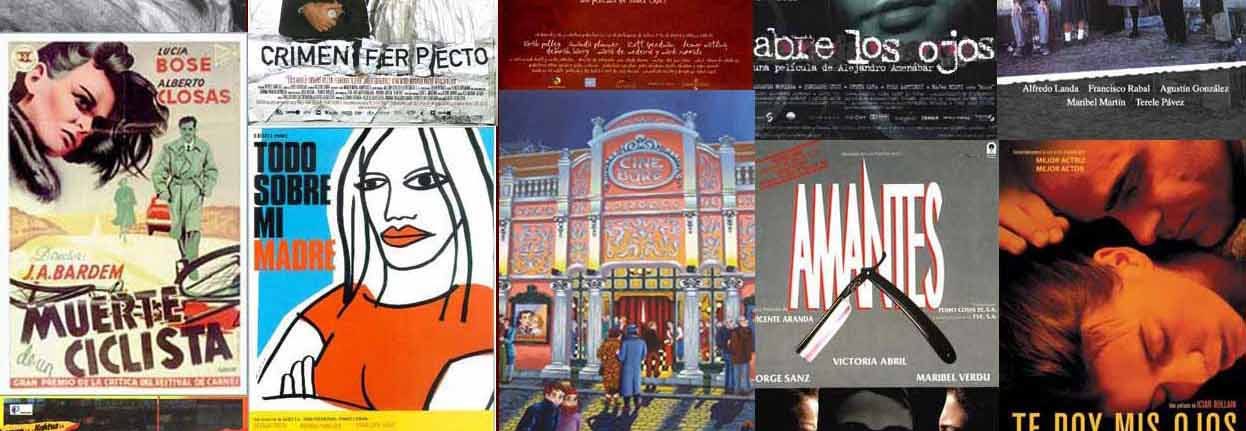

Juan Antonio Bardem, Muerte de un ciclista / Death of a Cyclist (1955)

- Opening and closing sequences

- “Aún está vivo” / “He’s still alive” (deep focus shot / plano en profundidad) (2’03”)

- “Tengo miedo” / “I’m frightened” (0’46”)

- Desenlace / Outcome (1): Muerte de Juan (Juan’s death scene)

- Desenlace / Outcome (2): Muerte de María José (María José’s death)

- Editing and camera work

- Cut: from Juan smoking to kiss (“Adivina, adivinanza…”) (1’05”)

- Cut from Rafa (“¿Algún amante?” / “Any lover?”) to Juan (0’15”)

- Cut to “Mi hermano Juan es un desastre” / “My brother is a disaster” (0’14”)

- Cut from Jorge at the party to Jorge on the newsreel (cinema) (1’02”)

- Cut from Juan to María José on smoke (0’06”)

- Cut from Rafa at the horse races to the circus (0’45”)

- Deep focus shot of student in class (0’02”)

- Montage: The math class (1’43”)

- Montage: Lucía Bosé y el entrelazamiento de psicologías (complicidad) (0’05”)

- Montage and deep focus shot: / Telephone conversation: “Nadie sabe nada” / “No one is aware” (1’04”)

- Intimate conversation Juan – María, cut to Miguel (0’47”)

- Deep focus shot of student in office with shot-reverse shot (0’34”)

- Long shot of Juan en la corrala (in the tenement housing) (0’43”)

- Cut from the “corrala” (tenement) to wedding (0’09”)

- Focus on thematics

- Juan with his mother: “La fama (familiar) en la vitrina” / “Our reputation is on stage” (1’08”)

- Pretense, façade: Juan and María in the fiesta (0’43”)

- Rafa as Harlequin

- Rafael “se explica” (he “interpretes” himself) (2’46”)

- Rafa and Juan in the restroom (1’23”)

- Deep focus shoot on roof: Rafa, Miguel and María José (0’31”)

- Cut: From an angry Rafa to the angry students (0’10”)

- Lucía Bosé: the star system and framing the performance

- Lucía Bosé “How do you spend your evenings when you away?” (0’26”)

- Lucía Bosé: “Miguel, vámonos pronto” / “Miguel, lets leave soon”)

- Lucía Bosé: “Cada día estás más bonita” / “You get prettier every day” (Jorge) (0’29”)

- Lucía Bosé: religiosa (con mantilla y peineta; 0’22”)

- Lucía Bosé: “tú harías cualquier cosa” (0’44”)

- Spectacle, performance and Flamenco

- Cut: “La solución, el próximo número” to “palmas” (0’15”)

- Flamenco montage (1’24”)

Carlos Saura, Cría cuervos (1975)

- Opening sequence to father’s corpse

- Combing Ana: Rosa, mother

- Ana’s imaginary suicide

- Ana’s first monolog as an adult: cut to Paulina at table with children

- Rosa cleans the glass through which Ana sees and the maid frames her vision of the past

- Truths and lies in the bathroom

- Ana’s second monolog as an adult: childhood

- From Jeanette to Imperio Argentina

- Constructing the feminine according to current models

- Seeing mother die

- From pistols to rat poison

- Ana’s stairs and banister (2)

- Reality and dreams: From Ana’s to her sister Irene’s

- Bridging the internal and the external: From Irene’s dream to the streets and on to school (finale)

Víctor Erice, El espíritu de la colmena (1973)

- Imaginary and real road into the story (1:51)

- Bees, beehives and interior monologues:

- Bridging fantasy and reality, childhood and adulthood:

- Poetry as bridge (5:39): echoes, poetry, mobility, landscape, symbolism, music, photography – References: Miguel de Unamuno; Federico García Lorca plays the Zorongo (“Tengo unos ojos azules…”) with Encarnación López La Argentinita on castenets

- Shadows (2:09)

- Art (1:42) – References: Saint Jerome / San Jerónimo: Aescetic, Doctor of the Church, translator of the Hebrew bible; themes: Memento mori and the vanitas)

- Nightime and the imagination / 2 (montage; 1:45): Ana’s mushrooms, music and the ashes of Teresa’s memories

- Imagining Frankenstein (2:43) – Reference: the 1931 Hollywood classic, Frankenstein, with Boris Karloff

- Isabel plays dead (6:07)

- Memory, history and representation: Ana, the maquis and Frankenstein

- The watch (1:10): concealing time, concealing history

- Irene’s offers Ana a lesson concerning the movies, “ghosts” and “spirits” (2:30)

- Montage (4:57): fading between (historical) reality and the imagination

- Epilogue: Ana applies what she has learned about representation, reality and the imagination (4:29)

Vicente Aranda, Amantes (1990)

Note: The popular songs that can be heard throughout much of the movie and that often serve as a sound bridge linking shots or sequences are most often Spanish Christmas carols. Here are a couple of orchestral versions of villancicos that resonate throughout Amantes: “En el portal de Belén, rin rin,…” and “Campana sobre campana…”. At times the melody of these songs is adapted expressively in the slow, sad violin music. Aranda incorporates at key moments a musical leitmotif that recalls the sound of the pandereta (a tambourine) that is traditionally used in Spanish villancicos, such as “Una pandereta suena” (“A Tambourine is playing”).

- Establishing the identities:

- Paco and Trini (0’48”) and (1’03”)

- Luisa

- The Balad of the Seductress fatale; from table to bed; (1’37”) (Note the variety of shots and film editing techniques used in this short sequence: Shot reverse shot, tracking shots, musical (sound) bridging, dissolves, zoom shot)

- Frontstage-backstage: hiding dirty business (3’48”)

- Linking, probing and embedding stories via the camera: Luisa and her buddies (2’02”)

- Establishing the when and where:

- Trini’s pueblo (02:11);

- Aranda de Duero (01:48; Check out the location on Google Maps)

- Locating Paco’s psychological struggle (0’23”)

- Nationalizing the noir / melodrama

- Cutting and tracking between the private and the public: Paco’s “Lord’s Prayer” (0’31”)

- Using the Christmas carol as a musical leitmotif (02:37)

- Cluing Paco’s conscience through camera effects and editing techniques (4’22”) Note: the music includes resonances of “Campanas sobre campanas,” a Christmas carol sung a various times throughout the movie, especially (and sadly) at the end

- Bloodied hands (1’02”)

Consider this famous quote from Shakespeare’s Macbeth in you analysis of this final sequence: “I am in blood Stepp’d in so far that, should I wade no more, Returning were as tedious as go o’er.?” (Act III, Scene 4)

- Aranda’s touch / 1: Food

- Aranda’s touch / 2: The geometry of social relations and passion; symmetries and triangulations

- Aranda’s touch / 3: Byways

- Stairs and portals lead Paco to his new abode (00:42)

- Asleep on the stairs (0’35”; shades of The Graduate?)

- Intersections and encounters, doors and stairs (1’53”)

- Passing through the byways of time, or time and interiority (1’13”)

Icíar Bollain, Te doy mis ojos / Take My Eyes (2003)

- Social formations: family, friends, community and individuals

- Pilar has a drink with her colleagues after work: musical bridge; exteriority and interiority; ironic contrast; windows (visual motifs); socio-economic formations and cultural values; relational meanings (cut to Antonio’s group therapy) (1’18”).

- Sisterhood: Pilar and Ana at Ana’s wedding (1’53”)

- Cut from marriage to men interacting at work (00’27”)

- Brotherhood: Antonio and his brother (00’48”)

- Symbolic moments, symbolic places: cemeteries, weddings, birthdays…

- Representation and reception: the utility of art, the power of the imagination

- Playacting as theraphy for the men: “Trata de ponerte en su lugar” (“Imagine that you are her”) (00’35”)

- Playacting as …?… for Pilar’s co-workers… and Pilar as spectator (01’09”)

- Luis de Morales, “Mater dolorosa” (Toledo Cathedral; 1579) (00’23”)

- Pilar explains Peter Paul Rubens’ “Orpheus and Eurydice”(Museo del Prado / Madrid) to her son; Antonio reenacts what the men performed in therapy (01’19”)

- An erotic interlude over Peter Paul Rubens’ “The Three Graces” (Museo del Prado / Madrid) and Antonio’s gift to Pilar (01’49”)

- Antonio struggles to represent himself > Antonio as spectator, while Pilar explain’s Titian’s “Danae“: perceiving dreams (2’23”)

- From diary to painting (1’39”; Wassily Kandinsky, “Composition VIII,” 1923)

- Pilar represents Antonio fears (Antonio’s diary) (01’01”)

- Between painting to pain: Antonio frames Pilar (2’06”)

- Final sequence: Pilar chooses photos that make sense; Antonio is left with a window onto a world that is hard for him to assimilate (2’33”)

- También la lluvia (Even the Rain; 2010): In this later movie by the same director, Icíar Bollaín, a Spanish film crew travels to Bolivia to shoot a motion picture about the Spanish conquest and the treatment of the natives in the 16th centure. In this particular clip, the actors, who are all local indigenous mothers, refuse to mime the drowning of their babies in the face of the “ficticious” onslaught of the conquistadores. What thematic resonance can you find between this scene and Te doy mis ojos (Take My Eyes)?

- The art of love (00’53”)

- Credits (at the end of the movie): the “Asociación de mujeres María Padilla de Toledo” (More news: 1 / 2

Mario Camus, Los santos inocentes / The Holy Innocents (1984)

- Film narrative: structuring the story audiovisually

- Family portraits

- Society

- Social linguistics (for Spanish speakers)

- “Tienes que echarle cojones” (0’18”)

- “Es mucha mariconería, ¿no te parece, Paco?” (0’18”)

- Dialog Paco – Iván (0’19”)

- (P) “El Quirce es campero, señorito, y tiene más luces que mi cuñado.

- (I) “Tampoco se puede decir que sea muy hablador.

- (P) ¡Así las gasta, señorito, cosas de la juventud!

- (I) ¡Qué coño quieren los jovenes de hoy, que no están a gusta en ninguna parte!

- “¿A que no tienes huevos, Paco, para salir mañana con el reclamo…?” (1’11”)

- Formal / stylistic elements

Pedro Almodóvar, ¿Qué he hecho yo para merecer esto? / What Have I Done To Deserve This? (1984)

- Pedro’s pastiche

- Tragic love story with consequences for the children

- Hollywood melodramatic points of reference: Douglas Sirk

- All That Heaven Allows (1955): Rock Hudson proposes marriage to Jane Wyman in a seclude cabin, in a wintry landscape

- Imitation of Life (1959): To make it big in the entertainment industry, Lana Turner has had to disguise her African-American roots; her reencounter with her mother is a classic Hollywood tear-jerker

- Music: Remembering the Españoladas, Folklóricas and Cupletistas

- Spain’s musical points of reference: different versions of the copla “La bien pagá” (see notes)

- This version, sung by Miguel de Molina in the 1952 classic Esta es mi vida, offers the best example of how popular music was incorporated in Spanish cinema during the 1950s as a form of distraction. Molina, stigmatized by the regime due to his homosexuality, ended up going into exile in Argentina. He returned to Spain one year before his death, in 1993, to receive a medal of honor for his contribution to popular culture (flamenco music and dance).

- Isabel de Pantoja is one of the most celebrated “copletistas” (caberet singers) in Spain.

- Jaime Chavarri includes a scene imitating Miguel de Molina singing “La bien pagá” in his 1989 hit Cosas del querer (The Things of Love)

- The Spanish-Cuban flamenco-jazz combo, Diego el Cigala and Bebo Valdés, have recorded what is, to date, the supreme version of this traditional heart-break melody of unrequited love.

- A few examples of Almodóvar’s irony:

- Lizzards and tragedy

Pedro Almodóvar, Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios / Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988)

- Opening sequence (2’50”)

- Study this highly stylized scene from Johnny Guitar, with Joan Crawford and Sterling Hayden, to see how Nicholas Ray‘s 1954 Hollywood classic informs Almodóvar’s masterpiece from the very start.

- Compare: the “gazpacho in the face” scene (1’54”)

- Musical interludes

- Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov / 1: Scheherazade: Dubbing a wedding ceremony (0’50“)

- Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov / 2: Capriccio Espagnol (4th movement: “Gypsy Song”): Consumed by the flames of one’s own passion (2’06”)

- Private Eye Pepa in action (2’13”)

- See notes regarding popular music in Almodóvar’s movies

- Star-crossed lovers crossing on the stairs (1’05”)

- Compare Aranda’s treatment of the same space and situation (1’53”)

- The television bridge (1’55”)

- Potential comparison with last sequence in Saura’s Cría cuervos? (1’42”)

- The palimpsest

- Candela’s mock suicide frames Pepa’s drama (2’03”)

- Story telling / Candela’s scam (1’44”)

- Tears in the taxi (0’53”)

- Ventriloquism: Carlos reading postcards (0’23”)

- Close encounters and hidden realities, or the hidden threads that are suitcases, telephones, and musical recordings (3’15”)

- The chase (2’37”)

- Compare Aranda’s portrayal of Paco’s progression toward his final destiny in Amantes (1’13”)

Pedro Almodóvar, Todo sobre mi madre / All About My Mother (1999)

- Intertextualities

- Location

- Musical bridges

- The cemetery scene (3’21”)

- Almodóvar uses a musical piece in the cemetery scene played on the Argentinian bandoneon (a type of acordeon), titled “Coral para mi pequeño y lejano pueblo” (“Coral for my small and distant town”). The composer is the Italo-Argentinian acordianist, Dino Saluzzi.

- Consider his use of Tajabone, by the Senegalese Ismael Lo, to bridge Manuel’s arrival in Barcelona (see above under “location”).

- Coordinating diverse diegetic levels of reference

- Manuela, the storyteller:

- Agrado’s monolog, in context (2’56”)

Pedro Almodovar, Volver (2004)

- Opening sequence: The song of the “Espigadoras” from the zarzuela La rosa del azafrán (2’06”; see notes on Amodóvar’s use of music in the “Supplementary” page).

- Raimunda makes a deal: Female solidarity developed around pork, chorizo (sausage), morcilla (blood sausage) and mantecados (a traditional cookie) (1’54”)

- Storytelling and intimacy (the woman as storyteller)

- Raimunda’s theme song tells the story in music (3’35”); the voice in this segment is that of the famous contemporary flamenco artist, Estrella Morente, whose version of “Volver” is has been a big hit in Spain.

- Final sequence: The anthropology of the house; “Ghosts don’t cry” (5’01”)

- The film reference in this final sequence is to a masterpiece of Italian neorealist cinema of the 1950s, Luchino Visconti’s Bellissima (1951; click here for trailer). Anna Magnani, the great Italian actress who stars in Roberto Rosselini’s Roma, città aperta (Rome, An Open City), portrays a desperate mother who tries any and everything to seek stardome –and material well being– for her daughter, in the glittery world of cinema. A heart wrenching story. Critics draw attention to Almodóvar’s attempts to model Penelope Cruz, through his film direction, on the Italian actress.

- Individuals and relations: The reverse shot (campo contra campo), closeups (planos de cara) and other related strategies

- Agustina and Sole during the funeral (0’57”)

Julio Medem, Los amantes del círculo polar

- Opening sequence (2’43”)

- The palindrome in a Deux Chevaux (2’32”)

- Love and the Arctic Circle (1’00”)

- Family portraits by day and by night (1’26”)

- Otto’s mother / flames and snow (5’27”)

- “Nunca he tenido el corazón tan rojo” (My heart was never so red!”) (2’22”)

- Historical memory: Guernica on the evening news (1’15”)

- From intertwined emotional and family crises to Madrid’s Plaza Mayor (4’25”)

- Photographs, families and serendipity: “Si os hubiérais llevado bien, como hermanos, esta casa seguiría siendo un hogar” (“If you had gotten along, as siblings, this house would still be a home”) (2’08”)

- Alvaro tells Ana about his father’s cabin in the Arctic Circle (0’33”)

- Guernica

- Ana’s journey to the seed (2’56”)

- Final sequence: 2nd version of Otto and Ana’s outcome with “Sinitaivas” by Olavi Virta & Harmony Singers (popular Finnish song) (1’49”)

- Bridges

- El corazón rojo (red hearts)

- Two passionate star-crossed lovers

- Planes

- El reno (the reindeer)

- Las antípodas (polar opposites)

Isabel Coixet, La vida secreta de las palaqbras / The Secret Life of Words (2005)

- The bookends

- Hanna and Joseph

- Memory, testimony and trauma: the shame of survival (4’50”)

- Other sequences

- Sequences from Mi vida sin mí (My Life Without Me; 2003)

- Opening sequence: interior monologue (1’30”)

- Ann’s (Sarah Polley) reflections in a diner after her cancer diagnosis (1’56”)

- Lee (Mark Ruffal9 in the laundromat: images of silence and revery (2’16”)

- Story telling 1: Ann’s neighbor’s nursing tale (2’50”)

- Story telling 2: Lee’s (John Berger’s To the Wedding) tale (2’16”)

- Ann’s final prayers (1’10”)

Alejandro Amenábar, Abre los ojos / Open Your Eyes (1997)

- The national and global traditions and influences that conjoin in Amenábar’s film

- Classical Spanish theater: Pedro Calderón de la Barca, La vida es sueño (1635, Life Is A Dream)

Read here about Segismundo’s “dream of life” as portrayed in Pedro Calderón de la Barca‘s masterpiece. - Classical global cinema / 1: Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958)

As Roger Ebert states, in Vertigo “a man has fallen in love with a woman who does not exist, and now he cries out harshly against the real woman who impersonated her.” See how Amenábar appropriates one of the signature moments in Hitchcock’s masterpiece. - Classical global cinema / 2: Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Cagliari (1921)

- Robert Wiene’s movie is a German silent (black & white) horror film that portrays a doctor-patient relationship not unlike Antonio and César’s in Amenábar’s movie. The somnambulist protagonist in Wiene’s masterpieces is named “Cesare.” Once awoken, he commits murders. He is also able to see both the past and the future. (Click here to see the movie.)

- Avant-garde European painting / 1: the Harlequin and the commedia del arte

The Harlequin or ‘Arlequín’ (in Spanish), as portrayed in modern painting, reveals the importance of the circus, clowns, masks, the carnavalesque and the world of the commedia dell’arte generally speaking for the European avant-garde.- Sofía as Pierrot (2’01”)

- Avant-garde European painting / 2: Surrealism:

Consider the visual correlations between the final shots in Abre los ojos and some of the paintings by the Belgian surrealist painter René Magritte. (See also “Magritte sky paintings.”) Does this suggest any possible basis for comparison with surrealism generally speaking and with the surrealist films and tendencies studied in our course in the movies of Luis Buñuel, or in the paintings of Salvador Dalí?- The final scene (3’30”)

- Classical Spanish theater: Pedro Calderón de la Barca, La vida es sueño (1635, Life Is A Dream)

- The plot structure

- Understanding César

- Location: Madrid

- The role of the therapist and voiceover:

- Representation & virtuality:

- Miscellaneous

- Tom Cruise helped to produce and acting along side his then partner, Penélope Cruz, in Vanilla Sky (see trailer), the 2001 American remake of Abre los ojos

Alex de la Iglesia, La comunidad / Common Wealth (2000)

- The programmatic prologue: the hidden, rotting cadaver

- Opening sequence (1’14”)

- Intertextuality: between global (genres) and a national esthetic

- Roman Polansi, The Tenant (1976)

- Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and George Lukas, Star Wars – A New Hope – IV (1977), The Empire Strikes Back – V (1980), The Return of the Jedi – VI (1983)

- “Fifteen Men on a dead man’s chest, Yo, ho, ho and a bottle of rum”: Between Domínguez (0’33”) and R.L. Stevenson’s model

- “Don Limpio tiene el secreto” / “Mr. Clean has the secret!”: newspaper clippings and television ads (1’30”):

- The architypal secret manuscript hidden in the attic (1’15”)

- (Social?) media: Jedi Knight needs princess for relationship (0’53”)

- Pirates of the Caribbean (with Johnny Depp and Keira Nightley) as an additional point of reference (trailer)

- Almodovar and female passion: Julia’s dilema (1’15”) through the lens of Pepa’s crisis (1’36”)

- Iconic Madrid:

- The quadriga atop Madrid’s Banco de Bilbao (1’13”)

- “El oso y el madroño” tavern in Old Madrid where justice and happiness ultimately prevail (2’08”)

- De la Iglesias’ humor:

- The theme of “community”:

- Emilio’s monologue / 1 – Present versus past, modernity against tradition: “We are a community, Julia!” (2’33”)

- Emilio’s monologue / 2 – The loyalty, solidarity, camaradier in moments of great fortune (the quiniela or sports lottery) (3’38”)

- The lottery has unique cultural significance in Spain. It represents something of a national holiday ritual, as exemplified by the National Christmas Lottery (la Lotería de Navidad), which people all over the country participate in large numbers in and which Spaniards at home and abroad follow closely in the press and on television. The official advertisements for the lottery are becoming increasingly creative. They tend to underscore the collective or communal nature of this national ritual. The use of children as the announcers of the premios (awards) in the official ceremony bestows upon the whole event the aura of benign innocence.

- Poetic justice: virtue against the vice of envy (1’45”)

- Connecting La comunidad to new understandings of national history, the past and the future in the year 2000

- The year in which La comunidad premiered in Spain, 2000, also marks the year that the journalist, Emilio Silva, located and disenterred from a mass grave (or ditch) the remains of his grandfather, who was murdered in 1936 at the beginning of the Civil War by elements loyal to Franco. Silva went on to found the award-winning and privately funded Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica, an organization that has tried to re-present the past by exhuming or bringing into the light of the day its spectres, what one journalist has termed the Ghosts of Spain. The most highly acclaimed ghost or spectre that continues to haunt the nation is that of Federico García Lorca, who was murdered unceremoniously for no reason other than his association with ideals and ideas that were antithetical to Fascism. To this day Lorca’s remains remain to be discovered. In an interesting newspaper article in 2000 the journalist Benjamín Prado wrote as follows: “Qué esconde la tierra que pisas, qué minerales, raíces, aguas ciegas o seres del subsuelo. Siempre me ha parecido inquietante pensar en ese mundo oscuro de debajo del mundo, pensar en esa tierra indescifrable donde el que cava puede encontrar una moneda antigua, un anillo perdido, una bala o un muerto. En España las balas y los muertos están por todas partes ” [“What does the ground that you trample hide, what minerals, roots, blind waters or underground beings? I’ve always been perplexed when thinking about that dark world underneath, when thinking about that indecipherable land where, if you dig, you might find an ancient coin, a lost ring, a bullet or a dead person. In Spain bullets and dead people are everywhere.”]

- The spectacle of horror and Julia’s gaze (1’30”): what is it about the way that the ghost in the attic is revealed, about the background to this ghost and about the story that unfolds concerning the dead neighbor that might allow us to conclude that in his own uniquely personal way Alex de la Iglesia offers a reflection on the past, the present and the future at a moment in which some Spaniards were seeking new ways to exhume forgotten wounds and process them according.

REVIEW MODULE

BEGINNINGS & ENDINGS

Luis Buñuel: Chien andalou (1928)

- Opening: 00:44

Luis Buñuel: Los olvidados (1950; The Young and the Damned)

Luis Buñuel: Viridiana (1961)

Luis Buñuel: El ángel exterminador (1962; Exterminating Angel)

Luis García Berlanga, ¡Bienvenido, Mr. Marshall! (1953; Welcome Mr. Marshall!)

Juan Antonio Bardem, Muerte de un ciclista (1955; Death of a Cyclist)

Carlos Saura, Cría cuervos (1975; Cría)

Víctor Erice, El espíritu de la colmena (1973; The Spirit of the Beehive)

Vicente Aranda, Amantes (1990; Lovers)

Icíar Bollain, Te doy mis ojos (2003; Take my eyes)

Mario Camus, Los santos inocentes (1984; The Holy Innocents)

Pedro Almodóvar: ¿Qué he hecho yo para merecer esto? (1984; What Have I Done to Deserve This?)

Pedro Almodóvar: Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios (1988; Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown)

- Opening: 00:54

Pedro Almodóvar: Todo sobre mi madre (1999; All about my mother)

Pedro Almodóvar: Volver (2004)

Julio Medem, Los amantes del círculo polar (1998; Lovers of the Arctic Circle)

Isabel Coixet, Mi vida sin mí (2003; My Life Without Me)

- Opening: 01:36

Alejandro Amenábar, Abre los ojos (1997; Open Your Eyes)

Alex de la Iglesia, La comunidad (2000; The Common Wealth)

DRAWINGS & DIARIES

Icíar Bollain, Te doy mis ojos (2003; Take My Eyes): Antonio’s diary

Isabel Coixet, Mi vida sin mí (2003; My Life Without Me): Ann’s diary

Alejandro Amenábar, Abre los ojos (1997; Open Your Eyes): César’s drawing pad and pencil

FORMALISM & REALISM

Excerpts

- Segundo de Chomón, Burgos (1911) and Les Kiriki: Acrobates japonais (1908)

Excerpts

- Luis Buñuel, Tierra sin pan (Land Without Bread; 1933) – and Chien andalous (1928)